Oaxaca, a coastal state in southern Mexico, is home to a significant number of indigenous cultures, including the Zapotecs and Mixtecs, and is also notable for its biological diversity, as measured by the variety of plant and animal species present. These resources and influences have contributed to Oaxaca’s position as a leading producer of handcrafts in Mexico. One of those resources in particular, a scale insect known as cochineal (Dactylopius coccus), is responsible for a strong red natural dye known as carmine. Extracts from cochineal have been used in Mexico since at least the fifteenth century (and in Peru for much longer), significantly impacted international trade during the Colonial Period, and continuing to be important in “coloring” our modern world.

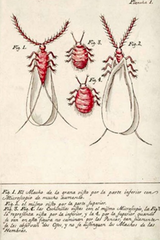

The cochineal insect makes its home on the paddles of the prickly pear (nopal) cactus. The nopal farms where they do this (nopalry) may use traditional or controlled methods, either of which involve the the female living approximately ninety days tucked into it’s protective waxy substance, and the (much smaller) males feeding only long enough to reproduce, then dying shortly thereafter. When it is time, the females are brushed off of the nopal paddles, and dried carefully, either in the sun for several days or using more industrial methods. Those carcasses are crushed and the brilliant red stain visible inside produces the carminic acid responsible for creating a range of brilliant reds, oranges and pinks. The color and shade produced depend on the production process and the chemical treatments used to finish the dye.

Cochineal was used by the Aztecs as a body paint, a dye for textiles and a medicine. After Cortez conquered the Aztecs, the importance and value of the red dye became recognized and began to be exported to Europe. While it has been a successful product in its native Mexican and South American climates, attempts to produce it in other parts of the world including Australia and Ethiopia, have not been successful.

Cochineal dye is expensive and scarce because of the number of insects needed to make it in quantity. Approximately 80,000-100,000 insects are needed to produce one kilogram (2.2 pounds) of dye, which is valued at $50-$80 USD. In the past, it was used rarely and only in the finest fabrics. In 1467, Pope Paul II announced that cardinals’ robes would be dyed red, rather than the traditional purple, by using the recently discovered dye. During the Revolutionary War, the “redcoats” or British soldiers, wore jackets dyed with cochineal.

In the nineteenth century, a synthetic dye called alizarin was developed, largely ending the economic power of cochineal trade. Both alizarin and cochineal extracts are currently used in food products, pharmaceuticals, laboratory stains, cosmetics and many other commercial products.

In this century, a strong interest in cochineal and its natural products has been revived. Many people yearn for the use of more natural substances over factory made chemicals. Some people have wondered about using cochineal for all red dye needs but have realized it would be nearly impossible and environmentally irresponsible, to use only natural dyes for all of the uses that humankind demands at this point.

Currently, there is a thriving production and use of cochineal in Oaxaca and Chiapas, Mexico and many other textile making regions of Latin America. Oaxaca and Chiapas are places where many textiles are still produced using traditional methods, and where embroidery is applied to beautiful textiles, making critical use of the brilliant reds, pinks, purples and oranges of this amazing substance. The extracts of cochineal affix more thoroughly and permanently to protein-based fibers than plant-based ones, making carmine an ideal dye for wool and silk products, and a beautiful way to add color to the garments produced in Mexico.

To see our current textiles from Oaxaca and Chiapas click on the photos or visit our website.